'Rod's Boat', Again

|

This post was updated on .

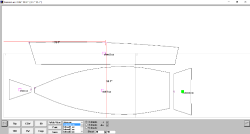

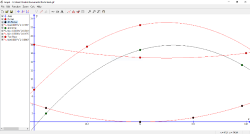

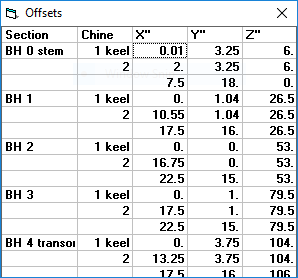

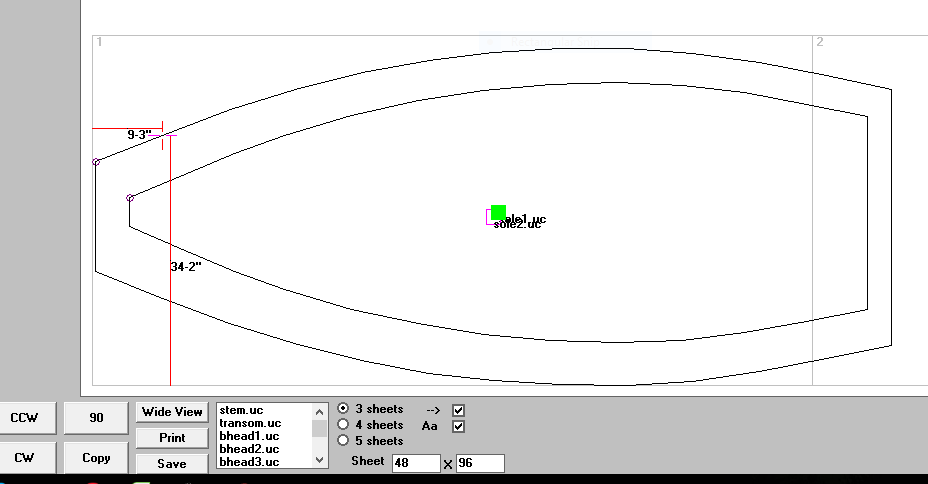

After a couple of days of fussing with lines, a drawing has emerged that I'd be willing to build. I'm calling it 'Rods' Boat', though I'm the intended user, because the boat is just a re-working of one I did a summer ago for a neighbor, follow rod-builder, and fly-fishing buddy.

Rod is 6'2” and 190. So I built the boat stout: 3/8” bottom, oak frames, etc., and it came in at 80 pounds. He's been in the boat just once at river trials on the Willamette, which isn't water where prams perform well. I used the boat last Spring on Lake Britton and was delighted with its performance. But I didn't like muscling 80 pounds up onto roof racks. So doing a lighter version has been on my mind. Three months ago, I fell from a ladder and busted my back. In the initial effort to re-configure my house for wheelchair use, I moved my boat shop out of my front room and back into my varnishing station, which is just a conventional wood-working shop. About the move my kids joked to one another, “Hey, did you know Dad had a front room?” And for about six weeks it was fun to have a conventional front room, all set up for reading. Then I started missing having immediate access to a boat in progress on a building frame. I've lost count of how many boats I've built that way. But it's the space where I prefer to work. Good lighting. Easy to heat. Immediately access to a kitchen and bathroom. Easy to keep clean for having wooden floors. Due to now being in a wheelchair, I rebuilt my saw horses lower, as well as simplified my clamp cart and tool chest. But the essentials are still there, which is a lofting table that becomes the building frame, for me preferring to build 'dory-style' (aka, right-side up).  To draw my boats, I use two tools: Greg Carlson's HULLS program and a freeware graphing program.   To build this (or any) boat, all that's needed is the offsets. Everything else (like crowning transoms, scuppering gunnels, the number and shape of the frames, timber choices, how the boat is planked) is just details that will vary from one builder to the next. The offsets are what matters and what determines performance on the water. In my case, I want a boat that's reasonably fast under oars (at least 4 MPH), offers high initial stability (for standing to cast). and is as light as possible for easy car-topping.  |

|

So, you're turning 'Rod's Boat' into 'Charlie's Boat.' Good idea! My brief row of 'Rod's Boat' let me know it's a good boat. Not just a good casting platform, but a good boat. I look forward to seeing your progress!

Mark |

|

Mark,

In my mind, what I'm going to build will always be 'Rod's Boat'. He was the inspiration for the design. It was his height and weight for which the boat was built. If I were to put my name to one of my designs, it'd be my smaller prams, e.g., the pair of boats I built for a summer camp. For their purpose --to be a kids boat for those who never rowed before-- and for their very efficient use of materials -- 1-1/2 sheets of ply, no scarfs-- they were a nearly perfect, flat-water boat. I hadn't had the first one in the water 30 seconds but knew I had gotten the design right, and a week of fishing them hard only confirmed that. Stable, fast, good looking. I'm still fretting about the beam of my proposed build. More beam enables longer oars. Longer oars enable a faster boat. But how 'fast' is 'fast enough' if the distance to be rowed --from launch to first cast -- is just a half mile? I really don't want to swing 8' oars, and even 7.5's are a bit long when a bass is on and headed for the bottom and oars need to be stowed out of the way of lines and nets. 7' foot oars --at 30% leverage with a 2" overlaps of the grips-- require (permit) a beam of 48". Right now --in one version-- my beam is 45". Going 3" wider is more weight. I need to think this one through. Charlie |

|

My beam worries are over. I'm going to trust my eye that I've got the lines right, never mind what the numbers might be. Thus, the designing phase of this build is done. Now I can start marking and cutting ply.

Is that a 'pram' or a 'skiff'? I'd call it a pram with a very tucked bow, and it will be built dory-style, right-side up, to which frames will be added once the open box is built. On 'Rod's Boat' (the original version), I used seven frames. On this version (meant to be lighter), I'll use just five. |

|

One of these years, I'm going to build myself a proper set of splining ducks. Meanwhile, I just raid my kitchen for soup cans or use clamps to position the batten on my station marks (done at 6" intervals).

One of the things I did do right years ago was to create a splining batten from 1/8" x 1/2" x 8' aluminum bar stock. The bar is flexible enough to describe a fair curve, but rigid enough not to take a set when stored, as would a wooden batten. What you're looking at in the photo is a full sheet of metric, 6 mil Occume on which I'm laying out the bottom, meaning, I can pick up an additional 2-7/16" of length versus what a sheet of 1/4" ply would offer. |

|

Bow and transom are now glued. Tomorrow, I'll be able to start hanging planks.

I'd like to be able to use the excuse of being crippled up to explain why it's taken me 16 days since last I posted on progress. But that's hardly the case. Just the demands of ordinary living cut into one's boat-building time. That, and some days just not wanting to work. But with the bow and transom now glued and curing, this build has definitely been launched, and its successful conclusion is all but assured, because all else about the boat depends on --and takes its shape-- from that start. It's just a guess at this point, but I'm thinking the boat will come in right at 23 kilos.

|

|

Planks are now dry-fitted. Now looking like a boat, and looking huge in my tiny work space.

|

|

Fillets are complete. I'm ready to install frames, gunnels, etc.

|

|

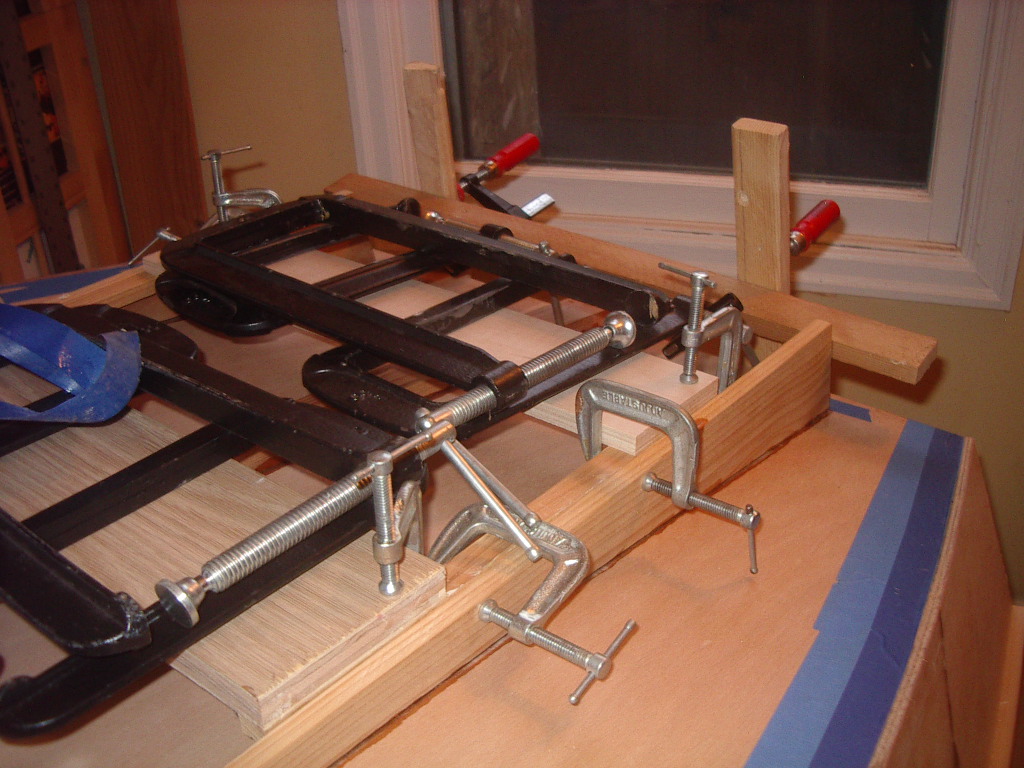

It took me 18.5 minutes to wet out and clamp the 52 scupper blocks using a 242 grains mixture of epoxy and hardener ('grains', not 'grams'), or an achieved assembly time of 21 seconds per block.

Why the need for speed? The reported pot life for West Systems epoxy using their 206 'fast harder' is 25 minutes. But I've found that it's prudent to set a timer for 20 minutes, and you'd better be setting your last clamp when the bell rings. The frames and scupper blocks are 5/8", fence board cedar that was planed to 0.500". Cheap, light weight, reasonable strong, and plenty good enough for a fishing boat. I used a cheap, Diablo blade to cut them and did no sanding nor easing of edges, as close inspection will reveal. But the fish don't care, nor do I.  |

|

Holy #*$@!! This has been a long, long building campaign.

I still have two days of clean-up before I can oil and varnish, plus I need to cut and fit oarlock blocks and a thwart. But that stuff's minor and fairly mindless. Put in the hours, and it will happen. This question occurred to me as I was finishing up the skegs. "By how much did the fact I'm a cripple --err, more properly, a T9-S2 partial paraplegic-- hinder assembling the boat in a timely, efficient manner?" Honesty would compel me to admit, "Not by very much." Boat-building just ain't fast, never mind claims by idiots like Payson that "instant boats" can be built. There's not a single part of building a boat that goes quickly, not if fits are to be tight and proportions not eye-jarring. The teams at the Beaufort Boat Building Challenge begin with unmarked ply and lumber and row a 12' skiff across a finish line 4 hours later. But my building time per foot of boat length is about 45x that, or 15 hours per foot instead of their mere 20 minutes. True, my hours include design work and finish work, neither of which the Beaufort building teams are doing, and their teams are two skilled, practiced craftsmen, and not just a single amateur in the shop. I've lost count of how many prams I've built, but the number's probably pushing toward a dozen. Every part of the job is easier for me than it once was. But the process of converting plywood and lumber into a boat still isn't a whole lot faster, not when each boat is different from the last in ways both subtle or large, so that each boat is 'one-off'. My urge last week was to immediately set up for my next boat once this one is carried out to my varnish station tomorrow. But I'm now thinking differently. Not only do I need a break from putting in long hours. I really should take the time to re-tool my front room shop, so that all and only the tools and machines I really need are easily at hand. That means building a clamp cart, a better means to shelf hand tools, a lumber rack. Then my next boat can begin. I was leaning toward reworking Bolger's Nymph, a boat I've built twice bfore. But what I really should build isn't yet another rowing pram, but a sailboat. I've got a vee-bottomed, double-knuckled pram sitting in my boson's locker that's an obvious candidate for conversion. Even better, the boat's sub-8'. So I could reclaim a bit of my front room. The conversion would mean installing a mast partner, side and aft bulkheads, a dagger board trunk, and building spars and a rudder assembly. Lots of wood working, but a break from boat-building, because the hull is sound and complete. As Hannibal --of A-Team fame-- used to say, "Sounds like a plan." -------------- Yes, my picture below of the skegs is puzzling. Why the jig? Why all the clamps? As you well know, once wood surfaces are smeared with glue, they slide. The jig keeps the doubled skegs parallel to each other and from sliding right off the bottom of the boat.  The hull --inside and out-- still needs scraping and sanding, and all edges need to be eased. A ton of assembly mistakes were made, some fairly significant. But the hard parts of completing a hull are now done, for better or worse, and everything wrong with this boat will get fixed in the next one.

|

|

With rain forecasted for later today, and some really nasty stuff coming in Sunday, I knew I had to get myself out to my shop to work on the boat while I could.

I turned on the heat, came back in for breakfast, and then geared up for sanding the interior. Chiefly, I ensured that the gunnel would be smooth to bare hands and corrected a nagging unfairness in the transom crown, but made short work of sanding the rest --roughly two hours of prep work in all-- before applying the first coat of oil. I ate lunch and then went back out to take care of the inevitable puddling and any dry spots. I know I've varnished in cold weather before without problems. But this time, my heart just wasn't into doing the work that vanishing requires, not when oil is so much faster and forgiving. So that will be how I finish the exterior as well. Yet to be done for the interior is cutting handholds in the bow and transom, cutting and fitting a thwart, fabricating and mounting oarlock blocks, and devising foot stretchers. But that stuff didn't need to be done before the boat was oiled.

|

|

Turning a boat over --even a nine footer weighing just 50 pounds-- is a two-man job if damage is to be avoided, or a one-man job and some rigging. A half dozen boats ago, I created overhead attachment points in my shop, so I could set up rigging for turning a hull in progress.

|

«

Return to General discussion

|

1 view|%1 views

| Free forum by Nabble | Edit this page |